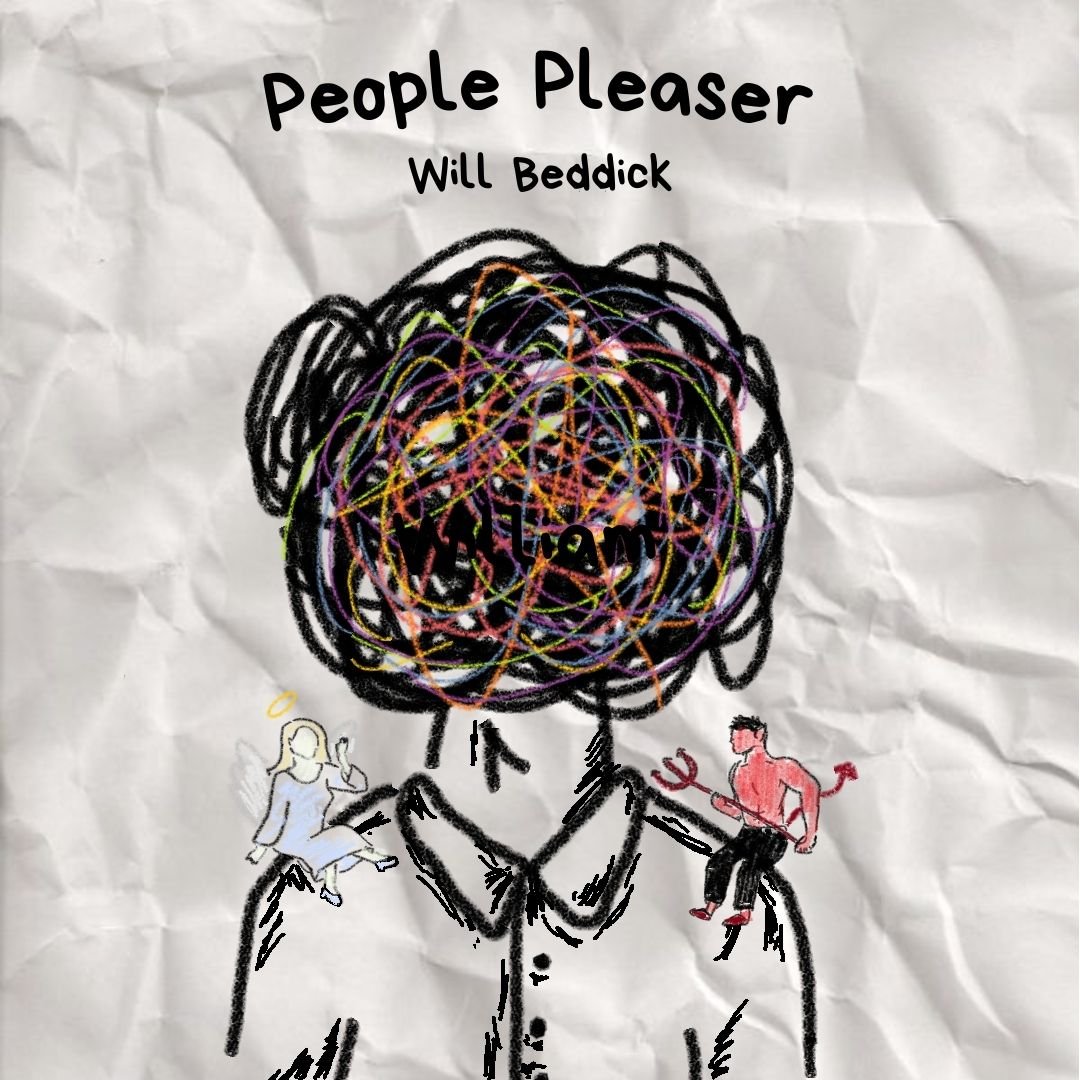

More often than not, you’ll probably find me with a bright smile on my face, laughing at a joke my friend made, giddily sharing a new song I found, or literally jumping up and down when I see a dog on the street. As a kid, my parents always told me I was their sunshine, I served to light up their world; and all my life I’ve carried that with me, trying to be the light and love in everyone’s life. Through that period, it looked very much like being a people pleaser: always playing the role of the happy and uplifting person in a situation, even when I felt the opposite. It felt as if, my best-served purpose, was to always be the positive one, but in doing that I was harming myself, and ultimately harming my relationships.

For a long time, the shards of my heart felt like they were held together with scotch tape, gradually peeling and falling away, barely holding anything together. Anxiety and depression are looming figures in my life, ones that are present even after I started going to therapy and taking medication. I allowed few others to see how it impacted me, afraid I would be unlovable, discarded, and no longer wanted if I couldn’t constantly be positive. I tried to hide the broken pieces of myself, afraid I would be too much, that I simply would stop fitting into people’s lives. I tried again and again to be this source of light when I myself felt surrounded by darkness. And eventually, I couldn’t do it anymore, I couldn’t hold the weight. My parents, my wonderful, lovely, supportive parents were the first to see this, to catch me as I started to fall and help pick me back up, again and again, each time I tripped. And they never failed to remind me that even as I struggled, I was still their sunshine.

And eventually, that struggle and that pain I had tried to conceal spilled out into my relationships outside of home, into my friendships. And let me tell you, it is hard to be vulnerable, to let others see that you’re struggling, especially when you want to hide it, especially when you’re trying to hold back this dam of pain to create room for the happiness of others. But I also know, and am reminded every day, that my best relationships were formed and/or became deeper, because I allowed myself to be vulnerable, because I found the best friends in the entire world who encouraged me to be vulnerable, who sat with me in the pain, who saw the tears I tried to hide, who had my back when I didn’t know if I could still stand. And who have made my life so much better because of it, have loved me better, and have in turn taught me to love deeper. Morgan, Celia, Ellie, Davin, Madeleine, Kylie, Hannah, and Lauren, oh how I love you so, I don’t know how I got especially lucky to be loved so well by all of you. The people who deserve you will stay, and they will make your life shine brighter because of it.

The truth is, when I finally let myself be who I truly was, I was able to love others more authentically. Allowing myself to share more of my pain and struggle let me have brighter joy, a fuller heart, and more genuine relationships. Learning that I didn’t need to always be the most positive person in the room lifted so much weight from my back, and allowed me to fall into the love of all the incredible people around me. When I got to college, I had that desire to hide away, but I was reminded of how much better friendships are when built on the foundation of presenting your true self. When Alison and Kaitlyn walked into my life, and quickly became two of my favorite people in the world, I gradually let my guard down and allowed myself to just be me, and our relationship is much stronger and lifegiving because of it. Existing at the fullest of who I am makes me feel more positive than trying to hide behind a mask of joy ever did.

But that vulnerability, that lowering of the mask, is still incredibly hard for me. My first instinct is still to opt for the positive response, to mask the pain I might be feeling–my anxiety and depression haven’t left me, they’ve just become better treated, better medicated, but not gone. It’s still often very hard for me to share big negative feelings, it takes more mental encouragement and effort on my part, but speaking it, even when it’s hard, always makes me feel better than the weight of keeping it in ever did. So, I keep making the decision, to be truly myself, to let that love in, so that I too can continue to offer love. I remind myself every day that I am loved, valued, and deserve to take up space. So here I am taking up that space, and letting the light in.

Written by Lauren Deaton

Edited by Julia Maynard and Elisabeth Kay