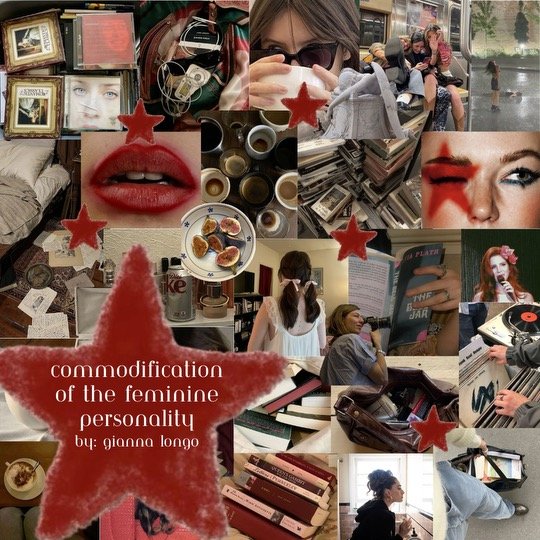

What is “cool” to you? What do you see in a person and immediately think, “Wow, I want to be their friend”? I argue that the concept of “cool” is nominal; though we see it everywhere–from the “Cool Girl” monologue in David Fincher’s Gone Girl (2014) to the influencers of TikTok telling us, flat out, which shoes are “cool girl,” which books make you a “thought daughter,” which movies make you “esoteric.” Abusive nomenclature is thrown around, most criminally and least tangibly on social media. Words once confined to academia are commonplace on all platforms, making a performance of pseudo-intellectualism among young women who feel pressure and influence to match this expectation of “cool.” As the definition changes, to be “cool” now is to be a mixture of smart and stylish–a nice, chic sense of dress paired with an appropriate popular culture. You are scoffed at for not knowing Fiona Apple, the Smiths, or Lana del Rey, laughed at if you don’t read Dostoevsky or Kafka or Camus, abhorred if you have never seen a Sofia Coppola film. Current internet culture omits that everything about you depends on how you appear, rather than who you actually are. If you can adequately show off things that you only seem to like, then you’ve won! Therefore, intellectualism and style become a mere commodity—an adornment of your personality rather than an actual facet of it.

However, women are placed at the firm center of this concept. So much of female personality is quantified by how we look, rather than what we like. Appearance for women has always been everything, even before the internet existed. The patriarchy has pushed this idea for centuries, and women have unfortunately fallen into its trap. Do we like what we like quietly, or do we publicly convey the things that we like only to a degree of acceptance? Who cares if you have not read all of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment if you can dress well and flaunt the novel like an accessory? Women are the primary victims of this newer “esoteric” phenomenon. Now, if you wear leggings, Uggs, don a slick back, and listen to Taylor Swift, you could face the threat of being called “basic.” Men, however, are essentially free from this struggle; they can express themselves with almost complete freedom without any pushback. Since they are the patriarchy, they are automatically accepted under it. There are, of course, exceptions to this, but men face less pushback on their aesthetic presentations than women do, at least on social media. All forms of media tell us that men want “weird girls,” a gross imitation of Ramona Flowers to fulfill their manic pixie dream girl fantasy. They want well-read, self-proclaimed “esoteric” women until they actually get one. You cannot fall too far on one side either; neither too basic nor too cool. Men are threatened by your being too much of one thing. If they begin to see your personality as a threat, they will throw you aside for the benefit of their own self-actualization.

It seems as if what you say you like is far more important than what you actually do. The pressure of having “good taste” is more important than ever, a pressure felt by many women in physical and online spaces. To be “cool” is a measure, sometimes, of being wanted. I ruminate on this idea with conversations that I have had with people in my life, including my best friend. We are both interesting, well-read, reasonably stylish women, yet we both speak about how we constantly feel the internal pressure to “be cooler,” or to conform our tastes so that we appear more interesting to the average eye. We both agree that it’s an exhausting ordeal, and both try to exorcize ourselves from these notions.

I did not fully flesh out this idea until recently, when in one of my classes we read a piece by Pierre Bourdieu titled “A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste.” In this writing, coming from his larger work Distinction, Bourdieu touches on the ideas of cultural and educational capital, as well as the existence of what he calls “legitimate taste.” He stipulates that those with the most “educational capital” are usually privy to distinguish what this “legitimate taste” is. Much like on social media now, the most educated, or the most objectively cool or “well-read” people, determine what is legitimate taste to the masses. Though Bourdieu’s descriptions of this err more on the side of critiquing capital in relation to production and consumer culture, his musings still ring true. The only difference now is that this “educational” or “cultural” capital comes from those who are viewed as conventionally attractive or traditionally “aesthetically pleasing” to the eye. Modern people obviously still care about capitalism and consumer culture, but less so than they care to admit, at least online. They take their advice on taste from the good-looking, well-dressed people they see on the internet. This further proves my point that it matters less now about your actual wealth of knowledge, but more so your general appearance and social status.

Likewise, social media has and always will exacerbate this problem. On watching one of my (admittedly) favorite movies of all time, The Social Network (2010), Jesse Eisenberg, posing as budding Mark Zuckerberg who is in the infancy of discovering what would become Facebook, laments to a freezing Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield) that Facebook will be cool because “people want to see what their friends are doing, who they hang out with, and that they are getting laid.” A crude statement, sure, but this eventually becomes the driving force of what creates Facebook. Even at the very inception of our modern version of social media, this idea of inherent performance was present. These very ideas laid the foundations for this performance-based posting, i.e. posing with The Communist Manifesto because it will win you brownie points.

That is not to say that I and many people I know are a victim of this. A lot of my tastes are not as honest as they could be. Sure, I really like bands like The Smiths, movies like The Godfather, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and writers like Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë. However, I also am impartial to “nerdy” things like Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter. I can enjoy objectively stupid movies like Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle, or read the YA books of Cassandra Clare or Rick Riordan. I can watch what people consider a “basic” show like Love is Blind without inherent shame and enjoy all of these things because they are a facet of me, not a facet of a premeditated design. We as media consumers toe a strange line between allowing women to be themselves, and being someone who tells them what they should be. Individuality is entirely at stake when we feel forced into this box of inherent performance. Women have never been able to like what they like fully and unashamedly. Everything we do as women is fiercely evaluated through an external gaze: through the patriarchal criticism of men or the pressured performance of social media. It is impossible to break free from this evaluation. Specifically, as young women, it is especially difficult to make this distinction between our actual selves and what we want others to perceive us as.

I don’t think there is a concrete answer to this, much less do I think that there will ever actually be one. As long as social media is a major presence in our lives, this query will unfortunately continue to exist. I do not mean to present this as a hate piece on social media or TikTok. In many ways, these types of platforms can inspire and even bolster creativity and individuality. However, as women especially, I think that we must be increasingly aware of the negative effects it has not only on our self-esteem but our sense of self in general.

I think that all humanity has every reason to express themselves freely without shame. The feminine personality is so commonly demeaned, rebuked, and forced into a binary that is constrictive and suffocating. Separating ourselves from this watchful eye and living freely, free of performance, is how we nurture our souls. Many people say that “to be a woman is to perform,” and our current social strata perpetuates this idea. In a number of ways, I feel myself so deeply intertwined with this awareness of self and of others that I have forgotten what I actually enjoy. Thus, I try to reintroduce myself to what I know, for a fact, I once loved. I encourage every young woman to return to your metaphorical “roots,” and regain the sense of self that you may have lost. The truth is, life is about re-remembering yourself. You change and morph into new versions of yourself so often that it is impossible to always and completely know who you are. Do not let social media force you into some version of what it thinks a woman should be or what a “cool woman” is; the coolest you can be is your true, genuine self. Be honest with who you are and people will admire you for it.

No Comments.